As a team, we set out to explore the question of why so many African American females seem to struggle in mathematics more than their peers. To address this question, we considered how the variables of being a minority and being female contribute to this divergence. The research shows that the fight for equality in education in this country has been going on for decades. Women and minorities have fought to have the same access to and success in the academic setting as white men, and yet African American females are still behind. Some might argue that the fault lies with the individual students. If they just worked harder and made mathematics a priority, they would have more success. No one is keeping them from choosing mathematics or math-related fields. However, our research indicates that this more of a systemic issue than that of individuals. That is, the “achievement gap” is better described as a “receivement gap”. If this population is not receiving the necessary support within the context of the educational system, it is the system that needs to be changed, not the students. Two major themes emerged from our research, tracking and self-confidence. While one can be described as external, and one as internal, in truth they are interwoven.

The first system considered in that of mathematics tracking. While there is not strong evidence supporting a causal connection between tracking and underachieving African American females, there is strong correlation between low-tracked classes and these students. The danger lies is student self-concept. Not surprisingly, students begin to associate their tracking level with their own ability. “Smart” students will be placed in higher classes, while “dumb” students will be placed in lower classes. Thus, the high numbers of African American females who find themselves in low-tracked classes are at risk of not believing they are capable of being successful in mathematics. While tracking may be utilized to provide specialized support to students of various mathematical levels, it can also have a detrimental impact on the self-confidence of certain populations within tracking.

Self-confidence was another focus. Research indicates that there are few role models of African American women mathematicians. Thus, African American students in mathematics may have difficulty visualizing themselves as being successful in this subject. Low standardized test outcomes may also strengthen the idea that African American women have no place in the mathematical arena. In addition to society’s influence in dissuading minority students from mathematical endeavors, these students’ own families and cultural groups may also play a role. Parents pass along their perspectives of the subject to the next generation. Students, not seeing themselves as having a part in this aspect of society, may choose to disengage. This disengagement can result in subtle or more direct defiance against the system they feel little attachment to. Research indicates that this lack of engagement may also express itself in dropping out.

Both of these systemic issues can be addressed with the singular idea of contextualizing the curriculum for these women of color. Much of the mathematics curriculum utilized in the school may not fit the social or cultural experiences of the students they are serving. Ladson-Billings (1995) refers to this as “culturally relevant pedagogy”. We encourage administrators and teachers to seek out resources with which African American females can more strongly identify.

This is not something educators and administrators must determine apart from their students and families. According to Poplin and Weeres (1992) “The transformation of America’s schools must and can only come from within” (p. unknown). Schools have to take time to listen to those they serve, and to those who work within their walls. When they took the time to listen they heard both adults and students “cry out for a say in what they are doing inside the schools and classrooms” (p. unknown).

As a result of listening to the communities being served and making the necessary changes, the experiences of students will be transformed for the better. If tracking is being used, low-tracked students will have more opportunity for success in mathematics and find the self-confidence and motivation to continue developing their skills. High-tracked students will also be able to continue growing, not having to work so hard to navigate between their cultural experiences and the coursework. If tracking is not used, this strategy still allows for greater success for a wider population of students. This will mean that educators will need to find ways of teaching mathematics that is outside their personal contextual norms. As mentioned in the self-confidence post, African American students may choose to express themselves in the classroom differently than their fellow classmates. Teachers need to broaden their perspective of an active learner, allowing them to better support a greater diversity of students. While challenging, this will be an opportunity for the entire academic community to be enriched in other ways of understanding the world, and the mathematics, around them.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally-relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 33(3), 465-491.

Poplin, M. & Weeres, J., (1992). Voices from the inside. Claremont, CA: The Institute for Education in Transformation at The Claremont Graduate School.

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Friday, May 27, 2011

A Conversation with African-American High School Women

I took the opportunity to interview a few of my female, African-American students about their personal experiences and self-expectations related to mathematics. Student A will be graduating with next year’s class and Student B is getting ready to graduate this June. As part of our school’s ongoing effort to implement various types of assessment tools that can be used to track student growth, both student took the MAP general mathematics test this past winter. At the time of the test, neither student was enrolled in a math course, due to the limited scheduling our small school has available. Student A’s scores were ranked at the 33rd percentile and Student B’s scores ranked at the 41st percentile in the national ranking. Of the 31 students tested, these students ranked fourth and third overall, respectively, in RIT score.

I began inquiring about their personal perspectives on mathematics and potential factors that influenced them. Student B expressed that she always felt good at math, and therefore liked it. She considered that her older sister who was enrolled in AP math courses as having positive impact on her perceptions of mathematics. Although, according to the student, the sister was ready to cheat in her advanced mathematics courses, she did encourage Student B to practice problems and work hard in mathematics. In continuing her reflection, Student B noted that in middle school she enjoyed mathematics because she felt she experienced a lot of success. Her high school math curriculum was based online, and she “didn’t recognize any of it” and felt confused. As a result, she admits that she just gave up.

Student A expressed that she had never felt confident in the subject. Student A said that she also had two sisters who were “good at math” but she said she could not recall a time that she felt “good” at it. She explained further that she could “do the work” but needed support to be successful. She does not like to work hard in a subject that does not come “natural” to her.

In looking towards the future, both seemed confident in their abilities and did not fear a lack of mathematical skill as being a barrier to their post-high goals and plans. Student A stated that although she did not consider herself good at it, she would be able to do what was required of her. This was reflected as we toured the Seattle Vocational Institute. At this site, students are required to pass an entrance exam in which they must show at least an eighth grade proficiency. Both students verbally expressed that they did not think that would be hard and seemed confident in their ability to successfully enter the programs for medical or dental assisting. According to the MAP norms, Student A is testing at about the eighth grade level, while Student B tested slightly higher, between the ninth and tenth grades.

An interesting theme emerges from this conversation, one that I have seem repeatedly in my years as a math educator in primarily minority student populations. Both students opinion of math was based on the level of difficulty. I wonder if “hard” means “not worth it” in other aspects of their lives, or if there is something unique to the context of mathematics. If these students do not see a viable purpose that affects their lives, it is understandable that once it no longer comes easily, there is no reason to continue. It seems that self-confidence could also influence their responses. When considering an “easy” concept, the labeling suggests they have the self-confidence to work until it is mastered. Once material becomes “hard” they lack belief in themselves that they can be successful if they apply themselves.

Source: www.nwea.org

I began inquiring about their personal perspectives on mathematics and potential factors that influenced them. Student B expressed that she always felt good at math, and therefore liked it. She considered that her older sister who was enrolled in AP math courses as having positive impact on her perceptions of mathematics. Although, according to the student, the sister was ready to cheat in her advanced mathematics courses, she did encourage Student B to practice problems and work hard in mathematics. In continuing her reflection, Student B noted that in middle school she enjoyed mathematics because she felt she experienced a lot of success. Her high school math curriculum was based online, and she “didn’t recognize any of it” and felt confused. As a result, she admits that she just gave up.

Student A expressed that she had never felt confident in the subject. Student A said that she also had two sisters who were “good at math” but she said she could not recall a time that she felt “good” at it. She explained further that she could “do the work” but needed support to be successful. She does not like to work hard in a subject that does not come “natural” to her.

In looking towards the future, both seemed confident in their abilities and did not fear a lack of mathematical skill as being a barrier to their post-high goals and plans. Student A stated that although she did not consider herself good at it, she would be able to do what was required of her. This was reflected as we toured the Seattle Vocational Institute. At this site, students are required to pass an entrance exam in which they must show at least an eighth grade proficiency. Both students verbally expressed that they did not think that would be hard and seemed confident in their ability to successfully enter the programs for medical or dental assisting. According to the MAP norms, Student A is testing at about the eighth grade level, while Student B tested slightly higher, between the ninth and tenth grades.

An interesting theme emerges from this conversation, one that I have seem repeatedly in my years as a math educator in primarily minority student populations. Both students opinion of math was based on the level of difficulty. I wonder if “hard” means “not worth it” in other aspects of their lives, or if there is something unique to the context of mathematics. If these students do not see a viable purpose that affects their lives, it is understandable that once it no longer comes easily, there is no reason to continue. It seems that self-confidence could also influence their responses. When considering an “easy” concept, the labeling suggests they have the self-confidence to work until it is mastered. Once material becomes “hard” they lack belief in themselves that they can be successful if they apply themselves.

Source: www.nwea.org

TED Talks- Salman Khan: Let's Use Video to Reinvent Education

This presentation discusses a unique way the internet is being used to support mathematics education. It allows students to work at their own pace and receive one-on-one support with their teachers. This may be a unique way for African American Female mathematics students to develop confidence as they master concepts incrementally, making sure no major gaps are being passed over.

TED Talk- Salman Khan Video

TED Talk- Salman Khan Video

Narrative Continued: Self-Confidence

There are many factors that affect how we feel about ourselves and about our abilities. When students are put in a position that undermines their abilities, there is research suggesting that self-confidence is one of the first causalities of failure. In the context of school and particularly math classes, where African American girls are preconditioned to feel as academic outcast there are additional reasons to feel inadequate.

Jae Hoon Lim (2008) quotes in her article The road not taken: Two African-American girls ‘experience with school mathematics, that the educational structure of our schools “help to maintain the status quo while marginalizing or disqualifying certain groups of people, such as women, minorities and members of low socioeconomic classes from positions of influence in society.” Research suggests that when you couple cultural identity with the current structure of our schools, girls are prevented from being motivated toward positive feelings (or having confidence in) math. With African Americans (across the diaspora) comprising less that 1% or all mathematicians and of this 1%, only 25% are women (State University of New York at Buffalo) students don’t have the options to see many role models and therefore could deduce that the possibility of their success in the field is negligible at best. According to the 2009 AMS report the percentage of underrepresented minorities graduate math students has been the same (10%) from 2004 thru 2009. This is not encouraging for increased representation of women or minorities at the primary or secondary school level where the motivation to teach is not bolstered by benefits such as tenure or treasure. Yes we do have some women of color in the field like Tasha Innis and Sherry Scott Joseph but these women are few and their influence is not very wide. Makes me wonder just how many individuals have been tracked out of the math field because they were female or belonged to a minority group.

In the same article Lim quotes Ogbu and Simons’ research that historically because of their race/ethnicity, groups have been “denied their intellectual capacities and potentials”, resulting in the defense mechanism of any oppressed group to their oppressor. Resistance. This resistance has come in the form of non-compliance, discipline issues (lack of respect) withdrawal and active/vocal dismissal. Every oppressed culture or group has had to develop means of survival. And as Freire points out “there may not be life or human existence without struggle and conflict” (Freire, 1997). Our African American students are struggling as well, for their academic future.

I have looked at Seattle Public schools with over 47,000 students to analayze data about minority groups, how many African American students stick around to graduate to have their potential tapped and to look at the districts report card on standardizing testing math scores. We will look at numbers on the graduation and drop-out rate of African Americans and draw conclusions on these students self-confidence.

African Americans: Graduate or Drop out?

The OSPI gathers the cumulative dropout rated for the entire state each year. In the 2009- 2010 school year, African American (or Black) students had the third highest dropout rate in the state (25.5%) yet they were only 2,703 of the 60,835 graduates’ statewide (Ireland, L. 2010). A student who is not in class cannot learn and certainly can’t keep up with their math. What is more disturbing is the dropout rate for African Americans is greater than for students in special education, low income, and migrant or on 504 plans (p. 20).

In the graduating class of 2010, the Seattle Public Schools reported a total of only 829 Black/African American students with a dropout rate was significantly lower, 6.5%, than in years before. This would appear to be a low percentage but when compared against other ethnicities and races African Americans student had the highest percentage of them all. Of these 829 enrolled African American students, 436 or 52.6% graduated in four years but 259 or 31.2% had dropped out by the end of the school year (this is a cumulative number using adjusted class numbers). It’s important to know what criterion is used to identify a student as a dropout.

“… A dropout is defined as a student who leaves school for any reason, except death, before graduation or completion of a program of studies and does not transfer to another school. An individual is a dropout whether dropping out occurs during or between regular school terms. A student who leaves during the year, but returns during the reporting period (including summer program) is not a dropout (Ireland, L. 2010).”

Why does it matter if or how many students of color or African Americans drop out of school? When a student routinely see their friends disappear or have had family members join this group, they are disenfranchised and affected by this pattern of departure and this in turns affect their motivation for school in general. This lack of motivation will affect all subjects but with math this can be especially egregious because it is a cumulative discipline and can be extremely difficult to catch up once the pattern of learning is broken. When a student has to “make up work” to catch up, it is a small step to lose your self-confidence and retreat to the cultural and stereotypical expectations of your ethic group.

Math Scores

Seattle Public Schools (SPS) issues a report card on how students are progressing on several academic markers including math. Looking at the math scores there was some interesting data. From what I could discern these are not reported or disaggregated by race or gender but if we were to look at each school, their minority enrollment statistics and low income reporting it would be possible to pull hard data. However for this entry we are going to look at the numbers district wide and make an educated assumption on how this might break down by race/ethnic group using anecdotal information.

The State of Washington and SPS have been using the WASL to address the federal NCLB standard with mixed results. There is wide consensus that the test is flawed as are most standardized testing because they are based on standards that do not take into account extraneous influences like family dynamics, social economic status, gender, poor teaching, inadequate instructional training or numerous other distractions.

Statewide 54.2% of 3rd thru 8 and 10th graders passed their WASL in math. In the state there are 672,350 white students and 56,790 Black/African American students just under 10,000 (9,704) of them in the Seattle Public Schools. The data indicates that African American are 8.6% of the total student population and Whites are 64.8%. If we take the percentage of students in all grades that passed the test and apply that percentage to the two racial/ethnic groups, then 363,069 or 54% White students passed the WASL and 30,666 or 53.9% African Americans passed (http://reportcard.ospi.k12.wa.us/summary.aspx?schoolId=100&OrgType=3&reportLevel=District&year=2009-10).

District wide 60.3 % of all high school students passed the math portion of the test. This means that 40 % did not. Using the same formula as we used with the State numbers – there are 20,506 White students and 9,704 Black/African American students. If 60.3% of ALL students passed and we used that number to generalize the percentages of White and Black students who passed the math test, then you would think that 12,300 White students and 5,820 Black/African American students passed . But this is not true. When you add gender and ethnicity, the actual numbers reported are 47.9% of all females passed and 16.3% of African Americans passed – the lowest percentage of all ethnic groups (Asians 53.4%, Latinos 30.4%, Native Americans 29% and Whites 69.8% (http:www.seattleschools.org/area/sisi/distsummary/2009/distcur.pdf).

These numbers and percentages look good for females but not for African Americans. Only 16% of all African Americans compared to almost 70% of all Whites passed this test last year. Not all of this is about race but it appears to be a big influence.

Where did Self-confidence go?

The historical educational inequality that parents experienced passes on from generation to generation and has the potential to greatly influences a students’ perception of their abilities especially in a discipline that is historically inflexible to experiential learning. These parents who had negative school experiences specifically with math are likely to pass on a discouraging attitude and accept their child’s belief that they are math incompetent or unaware that there are other ways to be math successful (Lim 2008).

If we couple the lack of parental support and loss of your social group through dropout or tracking, you create an unsafe place for students of color to risk moving out of their comfort zone and out of the lower level math classes. When all these come together, and sometimes you only need one of these deterrents, I believe it’s safe to say this has an effect on a students’ self-confidence and consequently their ability to compete in classes that required taking high risks to succeed.

Lim (2008) further points out that when you have the added dimension of teachers using observation of students as part of their assessment for higher level classes, African American students will not fare well as they do not operate as the model student – quiet, independently motivated and self-contained. The African American students’ “cultural frame of reference” to learning mathematics “entails a particular set of dispositions…such as working in support groups, accepting a free and expressive body movement and using a conversational style discourse in an instructional situation (Lim 2008).” The classroom set up to allow this cultural frame will go a long way toward a self-confident African American math student and dispel the feeling of self-inadequacy when faced with a challenging course.

There are women that have achieved the highest academic math status of PhD. But even some of them like Sherry Scott Joseph have had to overcome race and gender to become tops in her field. In speaking with Tasha R. Innis, another math professor she was quoted:

“ it is discouraging that there are so few women and minorities in mathematics and that progress in graduating more minority Ph.D.s has been so slow. The fighting doesn't stop. You still have to prove yourself,"

Etta Hollins (2010) sums it up in her letter to teachers Contextualizing Teaching and Learning:

“Through observation and interaction with my students I have come ot realize how much teachers influence the development, even transformation of their students as person. When a teacher is able to create a social context in the classroom in which each student feels accepted, appreciated and valued, students develop self-confidence and a sense of belonging as a member of the group.”

Black Women in Mathematics (2008) Retrieved from http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/PEEPS/scott_sherry.html

Freire, P. (2007) Teachers as cultural workers: Letters to those who dare teach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hollins, E. (2010). Contextualizing teaching and learning. In M.C. Fehr & D.E. Fehr (Eds.). Teach Boldly! (pp. 182-187). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Ireland, L. (2011). Graduation and Dropout Statistics for Washington in 2009-10. Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Olympia, WA. Retrieved from http://www.k12.wa.us/dataadmin/pubdocs/GradDropout/09-10/GraduationDropoutWashington2009-10.pdf

Lim, J. H., (2008) The road not taken: Two African-American girls’ experiences with school mathematics. Race Ethnicity and Education, 11:3, 303-317. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

Seattle Public Schools. Seattle, WA. Retrieved from http://www.seattleschools.org/area/siso/disprof/2010/DP10edstat.pdf

The Mathematics Department of the State University of New York at Buffalo. (1999 Jan). Retrieved from http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/wmad0.html

Jae Hoon Lim (2008) quotes in her article The road not taken: Two African-American girls ‘experience with school mathematics, that the educational structure of our schools “help to maintain the status quo while marginalizing or disqualifying certain groups of people, such as women, minorities and members of low socioeconomic classes from positions of influence in society.” Research suggests that when you couple cultural identity with the current structure of our schools, girls are prevented from being motivated toward positive feelings (or having confidence in) math. With African Americans (across the diaspora) comprising less that 1% or all mathematicians and of this 1%, only 25% are women (State University of New York at Buffalo) students don’t have the options to see many role models and therefore could deduce that the possibility of their success in the field is negligible at best. According to the 2009 AMS report the percentage of underrepresented minorities graduate math students has been the same (10%) from 2004 thru 2009. This is not encouraging for increased representation of women or minorities at the primary or secondary school level where the motivation to teach is not bolstered by benefits such as tenure or treasure. Yes we do have some women of color in the field like Tasha Innis and Sherry Scott Joseph but these women are few and their influence is not very wide. Makes me wonder just how many individuals have been tracked out of the math field because they were female or belonged to a minority group.

In the same article Lim quotes Ogbu and Simons’ research that historically because of their race/ethnicity, groups have been “denied their intellectual capacities and potentials”, resulting in the defense mechanism of any oppressed group to their oppressor. Resistance. This resistance has come in the form of non-compliance, discipline issues (lack of respect) withdrawal and active/vocal dismissal. Every oppressed culture or group has had to develop means of survival. And as Freire points out “there may not be life or human existence without struggle and conflict” (Freire, 1997). Our African American students are struggling as well, for their academic future.

I have looked at Seattle Public schools with over 47,000 students to analayze data about minority groups, how many African American students stick around to graduate to have their potential tapped and to look at the districts report card on standardizing testing math scores. We will look at numbers on the graduation and drop-out rate of African Americans and draw conclusions on these students self-confidence.

African Americans: Graduate or Drop out?

The OSPI gathers the cumulative dropout rated for the entire state each year. In the 2009- 2010 school year, African American (or Black) students had the third highest dropout rate in the state (25.5%) yet they were only 2,703 of the 60,835 graduates’ statewide (Ireland, L. 2010). A student who is not in class cannot learn and certainly can’t keep up with their math. What is more disturbing is the dropout rate for African Americans is greater than for students in special education, low income, and migrant or on 504 plans (p. 20).

In the graduating class of 2010, the Seattle Public Schools reported a total of only 829 Black/African American students with a dropout rate was significantly lower, 6.5%, than in years before. This would appear to be a low percentage but when compared against other ethnicities and races African Americans student had the highest percentage of them all. Of these 829 enrolled African American students, 436 or 52.6% graduated in four years but 259 or 31.2% had dropped out by the end of the school year (this is a cumulative number using adjusted class numbers). It’s important to know what criterion is used to identify a student as a dropout.

“… A dropout is defined as a student who leaves school for any reason, except death, before graduation or completion of a program of studies and does not transfer to another school. An individual is a dropout whether dropping out occurs during or between regular school terms. A student who leaves during the year, but returns during the reporting period (including summer program) is not a dropout (Ireland, L. 2010).”

Why does it matter if or how many students of color or African Americans drop out of school? When a student routinely see their friends disappear or have had family members join this group, they are disenfranchised and affected by this pattern of departure and this in turns affect their motivation for school in general. This lack of motivation will affect all subjects but with math this can be especially egregious because it is a cumulative discipline and can be extremely difficult to catch up once the pattern of learning is broken. When a student has to “make up work” to catch up, it is a small step to lose your self-confidence and retreat to the cultural and stereotypical expectations of your ethic group.

Math Scores

Seattle Public Schools (SPS) issues a report card on how students are progressing on several academic markers including math. Looking at the math scores there was some interesting data. From what I could discern these are not reported or disaggregated by race or gender but if we were to look at each school, their minority enrollment statistics and low income reporting it would be possible to pull hard data. However for this entry we are going to look at the numbers district wide and make an educated assumption on how this might break down by race/ethnic group using anecdotal information.

The State of Washington and SPS have been using the WASL to address the federal NCLB standard with mixed results. There is wide consensus that the test is flawed as are most standardized testing because they are based on standards that do not take into account extraneous influences like family dynamics, social economic status, gender, poor teaching, inadequate instructional training or numerous other distractions.

Statewide 54.2% of 3rd thru 8 and 10th graders passed their WASL in math. In the state there are 672,350 white students and 56,790 Black/African American students just under 10,000 (9,704) of them in the Seattle Public Schools. The data indicates that African American are 8.6% of the total student population and Whites are 64.8%. If we take the percentage of students in all grades that passed the test and apply that percentage to the two racial/ethnic groups, then 363,069 or 54% White students passed the WASL and 30,666 or 53.9% African Americans passed (http://reportcard.ospi.k12.wa.us/summary.aspx?schoolId=100&OrgType=3&reportLevel=District&year=2009-10).

District wide 60.3 % of all high school students passed the math portion of the test. This means that 40 % did not. Using the same formula as we used with the State numbers – there are 20,506 White students and 9,704 Black/African American students. If 60.3% of ALL students passed and we used that number to generalize the percentages of White and Black students who passed the math test, then you would think that 12,300 White students and 5,820 Black/African American students passed . But this is not true. When you add gender and ethnicity, the actual numbers reported are 47.9% of all females passed and 16.3% of African Americans passed – the lowest percentage of all ethnic groups (Asians 53.4%, Latinos 30.4%, Native Americans 29% and Whites 69.8% (http:www.seattleschools.org/area/sisi/distsummary/2009/distcur.pdf).

These numbers and percentages look good for females but not for African Americans. Only 16% of all African Americans compared to almost 70% of all Whites passed this test last year. Not all of this is about race but it appears to be a big influence.

Where did Self-confidence go?

The historical educational inequality that parents experienced passes on from generation to generation and has the potential to greatly influences a students’ perception of their abilities especially in a discipline that is historically inflexible to experiential learning. These parents who had negative school experiences specifically with math are likely to pass on a discouraging attitude and accept their child’s belief that they are math incompetent or unaware that there are other ways to be math successful (Lim 2008).

If we couple the lack of parental support and loss of your social group through dropout or tracking, you create an unsafe place for students of color to risk moving out of their comfort zone and out of the lower level math classes. When all these come together, and sometimes you only need one of these deterrents, I believe it’s safe to say this has an effect on a students’ self-confidence and consequently their ability to compete in classes that required taking high risks to succeed.

Lim (2008) further points out that when you have the added dimension of teachers using observation of students as part of their assessment for higher level classes, African American students will not fare well as they do not operate as the model student – quiet, independently motivated and self-contained. The African American students’ “cultural frame of reference” to learning mathematics “entails a particular set of dispositions…such as working in support groups, accepting a free and expressive body movement and using a conversational style discourse in an instructional situation (Lim 2008).” The classroom set up to allow this cultural frame will go a long way toward a self-confident African American math student and dispel the feeling of self-inadequacy when faced with a challenging course.

There are women that have achieved the highest academic math status of PhD. But even some of them like Sherry Scott Joseph have had to overcome race and gender to become tops in her field. In speaking with Tasha R. Innis, another math professor she was quoted:

“ it is discouraging that there are so few women and minorities in mathematics and that progress in graduating more minority Ph.D.s has been so slow. The fighting doesn't stop. You still have to prove yourself,"

Etta Hollins (2010) sums it up in her letter to teachers Contextualizing Teaching and Learning:

“Through observation and interaction with my students I have come ot realize how much teachers influence the development, even transformation of their students as person. When a teacher is able to create a social context in the classroom in which each student feels accepted, appreciated and valued, students develop self-confidence and a sense of belonging as a member of the group.”

Reference

AMS. (2009) Retrieved from http://www.ams.org/profession/data/annual-survey/2009Survey-Third-Report.pdf. (p. 1307). Black Women in Mathematics (2008) Retrieved from http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/PEEPS/scott_sherry.html

Freire, P. (2007) Teachers as cultural workers: Letters to those who dare teach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hollins, E. (2010). Contextualizing teaching and learning. In M.C. Fehr & D.E. Fehr (Eds.). Teach Boldly! (pp. 182-187). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Ireland, L. (2011). Graduation and Dropout Statistics for Washington in 2009-10. Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Olympia, WA. Retrieved from http://www.k12.wa.us/dataadmin/pubdocs/GradDropout/09-10/GraduationDropoutWashington2009-10.pdf

Lim, J. H., (2008) The road not taken: Two African-American girls’ experiences with school mathematics. Race Ethnicity and Education, 11:3, 303-317. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

Seattle Public Schools. Seattle, WA. Retrieved from http://www.seattleschools.org/area/siso/disprof/2010/DP10edstat.pdf

The Mathematics Department of the State University of New York at Buffalo. (1999 Jan). Retrieved from http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/wmad0.html

African American Women Mathematicians

Both Tasha Innis and Sherry Scott Jacobs are professors teaching at universities. They are both featured on the Mathematics Department of the State University of New York at Buffalo, African American Women In Math website. You can read about more women like them at http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/wmad0.html.

|

| Sherry Scott Joseph courtsey of Women In Mathematics |

|

| Tasha Innis courtsey of Women In Mathematics |

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Narrative Continued: Tracking Outcomes

Tracking, while supposedly designed to address student needs, seems in many cases to correlate with a gap between African-American and White students. Oakes (1990) states, “Assessments of academic ability, placement in different tracks or ability-grouped classes, and the reduced educational opportunities that characterize low-track classes often parallel race and social class differences” (vi). According to Hall, Davis, Bolen, and Chia (1999), after elementary school, African American students fall further and further behind each year.

Tracking seems to have differing outcomes which are dependent on the types of students being tracked and where they are placed. According to Powell and Berry (2007) the African-American male, middle school students they interviewed benefited from the tracking system because they were motivated by their advanced placement. One student was quoted as explaining that, “The smart kids make me work harder” (p. 172). Chambers (2009) interviews with male and female high school seniors and recent graduates revealed that all considered tracking a normal part of school culture. However, the authors note that as the students reflected on the entirety of their school experience, “Even at young school ages, these students began associating their ability placement with their intellect” (p. 423). That is high-tracked students considering themselves to be “smart” and low-tracked students considering themselves to be “dumb”.

Catsambis, Mulkey, and Crain (2001), whose study focused on the middle-school level, argue that the benefits of ability grouping may depend on a variety of factors, including the subject being taught and gender of the student. The correlation coefficients, outcomes of their research, “…indicate that students’ school-related attitudes and behaviors are affected by whether a school uses tracking or not. The effects, though, vary in relation to students gender and track level at which they are placed” (p. 98). Among students who tend to be tracked high or low, female students tend to have a stronger negative attitude towards mathematics than male students. In terms of self esteem and locus of control, tracking seems to be more impactful on males than females. Another outcome of the study indicated that female students in low tracking tended not to complete homework as much as their counterparts who were tracked at a high level. The authors (2001) theorize that this may be due to the fact that the low-tracked females feel that their track confirms their lack of confidence and give up. High-tracked female students complete more homework, maybe because they feel the need to work harder to keep up with their male peers, who, from their perspective, dominate the subject. Thus, it appears that the outcomes of tracking are dependent on the gender of the student and whether they are tracked as high or low.

In my personal experience as a math educator in an alternative setting, I have the opportunity with students who have struggled in mathematics. They enter my class at the beginning of the year full of fear, anxiety, or self-protective disinterest. The educational system as a whole, and sometimes educators in particular, have communicated to students that they are not capable of achievement in this area of study. Some have accepted this as truth. For these students my job as a teacher is to first find opportunities to students to feel empowered and capable in class. Traditionally, I have given these students tasks well below grade level so they can build up some belief in themselves as being able to succeed. After a period a time, students begin to say, “I got this!” or “This is easy!” To best meet their needs, it can be helpful to have them in class so we can work this process collectively. However, there is also the risk that in this “low-tracked” setting, they will continue to settle for the bare minimum of standards and never have a chance to see in their classmates how far they are capable of going.

I also have a more advanced class, where students are often exploring the same main concepts, but with slightly more challenging applications and faster pacing. I choose carefully those in this class, not just based on math capability, but their ability to persevere. These “higher-track” courses are not so much dependent on student capability, but confidence and willing to persevere. These students are not looking for the “easy” way out, but are willing to think through a problem, knowing they can reach a solution. Because tracking outcomes are dependent on the student and where they are tracked, it is important that, no matter how students are placed in class, they are given the opportunity to be successful and KNOW they are being successful. This self-confidence provides the foundation for a readiness to develop new understandings that reach beyond any predefined course expectations.

References

Catsambis, S., Mulkey, L. M., & Crain, R. L. (2001). For better or for worse? a nationwide study of the social psychological effects of gender and ability grouping in mathematics. Social Psychology of Education, 5(1), 83-115.

Chambers, T. (2009). The "Receivement Gap": School Tracking Policies and the Fallacy of the "Achievement Gap". Journal of Negro Education, 78(4), 417-431.

Hall, C., Davis, N., Bolen, L. & Chia, R. (1999). Gender and Racial Differences in Mathematical Performance. Journal of Social Psychology. 139(6), 677-689.

Oakes, R. (1990) Multiplying inequalities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. RAND, Santa Monica CA.

Powell, A., & Berry III, R. Q. (2007). Chapter Eleven: Achieving Success. In , Still Not Equal (pp. 167-175). Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Tracking seems to have differing outcomes which are dependent on the types of students being tracked and where they are placed. According to Powell and Berry (2007) the African-American male, middle school students they interviewed benefited from the tracking system because they were motivated by their advanced placement. One student was quoted as explaining that, “The smart kids make me work harder” (p. 172). Chambers (2009) interviews with male and female high school seniors and recent graduates revealed that all considered tracking a normal part of school culture. However, the authors note that as the students reflected on the entirety of their school experience, “Even at young school ages, these students began associating their ability placement with their intellect” (p. 423). That is high-tracked students considering themselves to be “smart” and low-tracked students considering themselves to be “dumb”.

Catsambis, Mulkey, and Crain (2001), whose study focused on the middle-school level, argue that the benefits of ability grouping may depend on a variety of factors, including the subject being taught and gender of the student. The correlation coefficients, outcomes of their research, “…indicate that students’ school-related attitudes and behaviors are affected by whether a school uses tracking or not. The effects, though, vary in relation to students gender and track level at which they are placed” (p. 98). Among students who tend to be tracked high or low, female students tend to have a stronger negative attitude towards mathematics than male students. In terms of self esteem and locus of control, tracking seems to be more impactful on males than females. Another outcome of the study indicated that female students in low tracking tended not to complete homework as much as their counterparts who were tracked at a high level. The authors (2001) theorize that this may be due to the fact that the low-tracked females feel that their track confirms their lack of confidence and give up. High-tracked female students complete more homework, maybe because they feel the need to work harder to keep up with their male peers, who, from their perspective, dominate the subject. Thus, it appears that the outcomes of tracking are dependent on the gender of the student and whether they are tracked as high or low.

In my personal experience as a math educator in an alternative setting, I have the opportunity with students who have struggled in mathematics. They enter my class at the beginning of the year full of fear, anxiety, or self-protective disinterest. The educational system as a whole, and sometimes educators in particular, have communicated to students that they are not capable of achievement in this area of study. Some have accepted this as truth. For these students my job as a teacher is to first find opportunities to students to feel empowered and capable in class. Traditionally, I have given these students tasks well below grade level so they can build up some belief in themselves as being able to succeed. After a period a time, students begin to say, “I got this!” or “This is easy!” To best meet their needs, it can be helpful to have them in class so we can work this process collectively. However, there is also the risk that in this “low-tracked” setting, they will continue to settle for the bare minimum of standards and never have a chance to see in their classmates how far they are capable of going.

I also have a more advanced class, where students are often exploring the same main concepts, but with slightly more challenging applications and faster pacing. I choose carefully those in this class, not just based on math capability, but their ability to persevere. These “higher-track” courses are not so much dependent on student capability, but confidence and willing to persevere. These students are not looking for the “easy” way out, but are willing to think through a problem, knowing they can reach a solution. Because tracking outcomes are dependent on the student and where they are tracked, it is important that, no matter how students are placed in class, they are given the opportunity to be successful and KNOW they are being successful. This self-confidence provides the foundation for a readiness to develop new understandings that reach beyond any predefined course expectations.

References

Catsambis, S., Mulkey, L. M., & Crain, R. L. (2001). For better or for worse? a nationwide study of the social psychological effects of gender and ability grouping in mathematics. Social Psychology of Education, 5(1), 83-115.

Chambers, T. (2009). The "Receivement Gap": School Tracking Policies and the Fallacy of the "Achievement Gap". Journal of Negro Education, 78(4), 417-431.

Hall, C., Davis, N., Bolen, L. & Chia, R. (1999). Gender and Racial Differences in Mathematical Performance. Journal of Social Psychology. 139(6), 677-689.

Oakes, R. (1990) Multiplying inequalities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. RAND, Santa Monica CA.

Powell, A., & Berry III, R. Q. (2007). Chapter Eleven: Achieving Success. In , Still Not Equal (pp. 167-175). Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Monday, May 23, 2011

Who is Smarter In Math?

As part of my interview with Katy's class I asked her students who told them who was smarter in math. Take a look at this short video where the students share who has their backs and shares their opinion.

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Interview Katy Lungren Pence 4th Grade Class

Leschi Elementary in Seattle’s Leschi/Madrona Neighborhood

When you have not been into a 4th grade classroom for quite a while, you can be thoroughly intimidated by the depth of thinking possible for kids so young. When I walked into Katy’s class at Leschi elementary I thought I knew how to handle kids. And I do but I’m not as good as I thought I was. So I went in thinking I would have a certain set of questions and after spending time in their environment, watching them teach each other WASL math, move from learners to teachers and “turn and talk” I knew my original plan wouldn’t work. So I punted. Following is the account of my 30 minute visit and 10 minute talk to these engaging students starting with some statistics on the neighborhood, the school and then my interview results.

Leschi elementary is located on the border of the Central District in Seattle’s Leschi/Madrona neighborhood. Originally surrounded by working class modest homes the neighborhood has undergone a fairly significant change over the past 15 – 20 years. To get a picture of the two I’ve created a simple table of information I think is interesting. I included information on both neighborhoods to illustrate the difference a few thousand dollars can make.

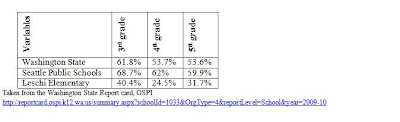

Leschi school is not reflective of the neighborhood surrounding it. As of May2010 they reported 68.3% of their students as Black and 14.7% as White. Seventy three point three percent of their students are on free or reduced-price meals, 11.5% special ed. and 17.3% are transitional bilingual. What is particularly interesting to me and the reason why I visited was to gage one class of students interest and instruction in math. According to their 2009-10 MSP tests 40.4% of 3rd graders, 24.5% of 4th graders and 31.7% of 5th graders have met the standard for math. This is considerably lower that the district where 68.7% of 3rd graders, 62% of 4th and 59.9% of 5th graders have met the standard in the Seattle Public schools. Again let’s compare Leschi against other Seattle Public Schools and the State of Washington scores.

So my expectations were not low nor were they neutral. I go in thinking school with a history of poor test scores, students not transitioning into highly competitive programs, parents association (PTA) historically non-existent. So I walk into this class of what, 27 kids, ALL of them with brown faces. One of the brown faces wasn’t African or African American but he wasn’t white either. From the minute I walk in they are engaged, working in groups or individually, on task and on point. There was a notable absence of unproductive chatter and unnecessary movement. This class moved my perception from neutral to positive.

So I get to watch these students figure out the area of shapes using L x W on shapes that look like a capital T, dividing the illustration into two smaller rectangles and making it work. Great. They’re smart and creative. Now it’s my turn and I ask them a series of questions that I’ve pulled out of nowhere. Not the way we’re supposed to conduct an interview but it’s the best I could do. I’m going to talk about the ones that I really came to ask and not the ice breakers.

1. What is your favorite subject?

2. Why is it your favorite subject?

3. Who told you were good at it?

4. Are girls smarter than boys at math? Why?

5. Are boys smarter than girls at math? Why?

6. How do you get better at math?

7. What do you want to be when you grow up?

Now I told the students I would take notes because I’m old and I don’t remember much, but I forgot to take notes so this is what I remember as striking.

1. What is your favorite subject?

This ran the range of lunch, recess, PE, Language Arts, Reading and at least 6 girls and boys saying Math.

2. Why is it your favorite subject?

The best response was predictable, “because I’m good at it.” But other responses were because they liked it or it was fun.

3. Who told you were good at it?

Most of the students said their mother, father, parents or other family members. At least three students said themselves. They had decided they were good and they encouraged themselves to be good in their favorite subject. None of the kids who said themselves had answered that their favorite subject was PE, Art, lunch or recess. All of them had offered an academic class so they believed themselves to be stars in these subjects. Great self-esteem.

4. Are girls smarter than boys at math? Why?

All but one girl raised her hand and she looked around to see she was alone on this one. What was more interesting is that there were a couple of boys that agreed with them at least until I asked the next question and then they had to support their partners. They girls believed they were smarter because they didn’t waste time on things like video games and sports.

5. Are boys smarter than girls at math? Why?

Not only are they smarter, they don’t worry about things like hair and nails either. They were rock solid convinced BUT I think they knew that if there was a real competition they might lose. This was because one girl suggested we do just that. She said that we should have a math-off competition and the loser would have some consequence – don’t remember what it was but it was good.

6. How do you get better at math?

Every single kid believed that they could get better and it took focus, hard work, paying attention, coming to school, asking questions and doing the best they could. Not one kid believed they couldn’t get better and I didn’t see any evidence of feeling inferior even when I know some of those kids were getting one on one instruction because I saw it.

7. What do you want to be when you grow up?

This was a smokescreen to see if anyone said mathematician. They didn’t. But doctor, lawyer, Indian chief weren’t the only choices either. These students were confident in their ability to be successful because they understood the concept of working hard and being focused. We did talk about what they thought was a distraction to getting their work done and there were a few that responded with predictable answers. The one student that could have said “babysitting” or 19 people in the home raised her hand but when the previous answers didn’t lean that way, I don’t think she was comfortable revealing the chaos in her home either.

So what did I get from this exercise? Teachers matter. The fact that this teacher is a hard core math task master (not really but she expects and gets great results) makes a difference. If you know your subject and can make it engaging (she did), make it fun (she did) and get kids to feel successful (she did) they want to learn and they want to shine. And they did.

When you have not been into a 4th grade classroom for quite a while, you can be thoroughly intimidated by the depth of thinking possible for kids so young. When I walked into Katy’s class at Leschi elementary I thought I knew how to handle kids. And I do but I’m not as good as I thought I was. So I went in thinking I would have a certain set of questions and after spending time in their environment, watching them teach each other WASL math, move from learners to teachers and “turn and talk” I knew my original plan wouldn’t work. So I punted. Following is the account of my 30 minute visit and 10 minute talk to these engaging students starting with some statistics on the neighborhood, the school and then my interview results.

Leschi elementary is located on the border of the Central District in Seattle’s Leschi/Madrona neighborhood. Originally surrounded by working class modest homes the neighborhood has undergone a fairly significant change over the past 15 – 20 years. To get a picture of the two I’ve created a simple table of information I think is interesting. I included information on both neighborhoods to illustrate the difference a few thousand dollars can make.

Leschi school is not reflective of the neighborhood surrounding it. As of May2010 they reported 68.3% of their students as Black and 14.7% as White. Seventy three point three percent of their students are on free or reduced-price meals, 11.5% special ed. and 17.3% are transitional bilingual. What is particularly interesting to me and the reason why I visited was to gage one class of students interest and instruction in math. According to their 2009-10 MSP tests 40.4% of 3rd graders, 24.5% of 4th graders and 31.7% of 5th graders have met the standard for math. This is considerably lower that the district where 68.7% of 3rd graders, 62% of 4th and 59.9% of 5th graders have met the standard in the Seattle Public schools. Again let’s compare Leschi against other Seattle Public Schools and the State of Washington scores.

So my expectations were not low nor were they neutral. I go in thinking school with a history of poor test scores, students not transitioning into highly competitive programs, parents association (PTA) historically non-existent. So I walk into this class of what, 27 kids, ALL of them with brown faces. One of the brown faces wasn’t African or African American but he wasn’t white either. From the minute I walk in they are engaged, working in groups or individually, on task and on point. There was a notable absence of unproductive chatter and unnecessary movement. This class moved my perception from neutral to positive.

So I get to watch these students figure out the area of shapes using L x W on shapes that look like a capital T, dividing the illustration into two smaller rectangles and making it work. Great. They’re smart and creative. Now it’s my turn and I ask them a series of questions that I’ve pulled out of nowhere. Not the way we’re supposed to conduct an interview but it’s the best I could do. I’m going to talk about the ones that I really came to ask and not the ice breakers.

1. What is your favorite subject?

2. Why is it your favorite subject?

3. Who told you were good at it?

4. Are girls smarter than boys at math? Why?

5. Are boys smarter than girls at math? Why?

6. How do you get better at math?

7. What do you want to be when you grow up?

Now I told the students I would take notes because I’m old and I don’t remember much, but I forgot to take notes so this is what I remember as striking.

1. What is your favorite subject?

This ran the range of lunch, recess, PE, Language Arts, Reading and at least 6 girls and boys saying Math.

2. Why is it your favorite subject?

The best response was predictable, “because I’m good at it.” But other responses were because they liked it or it was fun.

3. Who told you were good at it?

Most of the students said their mother, father, parents or other family members. At least three students said themselves. They had decided they were good and they encouraged themselves to be good in their favorite subject. None of the kids who said themselves had answered that their favorite subject was PE, Art, lunch or recess. All of them had offered an academic class so they believed themselves to be stars in these subjects. Great self-esteem.

4. Are girls smarter than boys at math? Why?

All but one girl raised her hand and she looked around to see she was alone on this one. What was more interesting is that there were a couple of boys that agreed with them at least until I asked the next question and then they had to support their partners. They girls believed they were smarter because they didn’t waste time on things like video games and sports.

5. Are boys smarter than girls at math? Why?

Not only are they smarter, they don’t worry about things like hair and nails either. They were rock solid convinced BUT I think they knew that if there was a real competition they might lose. This was because one girl suggested we do just that. She said that we should have a math-off competition and the loser would have some consequence – don’t remember what it was but it was good.

6. How do you get better at math?

Every single kid believed that they could get better and it took focus, hard work, paying attention, coming to school, asking questions and doing the best they could. Not one kid believed they couldn’t get better and I didn’t see any evidence of feeling inferior even when I know some of those kids were getting one on one instruction because I saw it.

7. What do you want to be when you grow up?

This was a smokescreen to see if anyone said mathematician. They didn’t. But doctor, lawyer, Indian chief weren’t the only choices either. These students were confident in their ability to be successful because they understood the concept of working hard and being focused. We did talk about what they thought was a distraction to getting their work done and there were a few that responded with predictable answers. The one student that could have said “babysitting” or 19 people in the home raised her hand but when the previous answers didn’t lean that way, I don’t think she was comfortable revealing the chaos in her home either.

So what did I get from this exercise? Teachers matter. The fact that this teacher is a hard core math task master (not really but she expects and gets great results) makes a difference. If you know your subject and can make it engaging (she did), make it fun (she did) and get kids to feel successful (she did) they want to learn and they want to shine. And they did.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Narrative Continued: Background from Other Perspectives

For many years, educators, politicians, and community groups have been attempting to explain and resolve the issue of why minorities, including African American females, struggle in mathematics. This issue is commonly known as the “achievement gap”. Chambers (2009) argues that this term carries with it a negative connotation. It implies that the dominant race of students is superior in some way to the minority students. That is, they are achieving more than the students that are represented by the lower end of the gap. While the education system as a whole preaches on the equality of all students, the label of this disparity places the blame on students, not the education system. The author, in an attempt to refocus the responsibility, suggests another term, the “receivement gap”, to describe this phenomenon. Chambers (2009) states, “The term ‘receivement gap’ is useful because it focuses attention on educational inputs—what the students receive on their educational journey, instead of outputs—their performance on a standardized test” (p. 418). While some authorities may not overtly argue that students should be held responsible to achieve more, the name chosen suggests the existence of a culture within education that excuses itself from taking responsibility of the issue.

Stenson (2006) also recognizes that inequality can be considered as the result of “receivements”, or inputs, not just the individual student. He argues that mathematics education can be better understood not just through the narrow lens of educational research, but also through anthropology, social psychology, sociology, and sociopolitical critique. He references the charts below as a way of considering the different influences that impact African-American’s mathematical achievement. Stenson (2006) maintains that, “… for critical postmodern researchers who are focused on issues of equity and social justice within education, specifically in the mathematics classroom, the critiques of mathematics education become much broader than those that are found within the confines of the students <à teachers <à material technologies (e.g., mathematics curriculum) instructional triangle” (p. 479). Thus, educators who choose not to look beyond their classroom are limited in their ability to meet their student needs.

Tate (2008) gives a specific example of how the lens of sociology could be utilized to examine these varying influences. With the launch of Sputnik, mathematics became a key focus of the United States educational objectives. However, this transformation applied mostly to the “college capable” student, focusing the reforms on only some students and communities. “According to L. S. Miller (1995), educational attainment is a function of the quality of education-relevant opportunity structure over several generations. The pace of educational advancement depends on multiple generations of children attending good schools. Thus, reform efforts targeted for students perceived as college capable merely accelerate the intergenerational resource value-added of largely White, middle-class, suburban students deemed college ready (Shapiro, 2004). This is not to say these students should be denied opportunity structures, such as high-quality teachers; rather, it indicates the importance of providing qualified teachers to less affluent communities and demographic groups that have been traditionally underserved in mathematics.” (Tate, 2008,p. 954). By looking at the mathematical success through this larger social construct, more influences that impact the African-American mathematics student become apparent.

In addition to understanding this issue from a sociological perspective, an economic perspective can also be considered. Banks (2008) explains that as this country grows more and more diverse, higher percentages of the student body will be minority students. Eventually, this higher percentage will translate to a higher percentage in the workforce, an arena where problem-solving and critical thinking are imperative. Banks (2008) predicts that, “If these labor trends continue, there will be a mismatch between the knowledge and skill demands of the workforce and the knowledge and skills of a large proportion of U.S. workers.” Thus, the dilemma of minorities ill-equipped for the jobs of today and tomorrow because of their lack of mathematics skills could be an important economic consideration.

References

Banks, J. (2008). An introduction to multicultural education. Boston: Pearson.

Chambers, T. (2009). The "Receivement Gap": School Tracking Policies and the Fallacy of the "Achievement Gap". Journal of Negro Education, 78(4), 417-431.

Stinson, D. W. (2006). African American Male Adolescents, Schooling (and Mathematics): Deficiency, Rejection, and Achievement. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 477-506.

Tate, IV, William F. 2008. "The Political Economy of Teacher Quality in School Mathematics: African American Males, Opportunity Structures, Politics, and Method." American Behavioral Scientist 51, no. 7: 953-971.

References

Banks, J. (2008). An introduction to multicultural education. Boston: Pearson.

Chambers, T. (2009). The "Receivement Gap": School Tracking Policies and the Fallacy of the "Achievement Gap". Journal of Negro Education, 78(4), 417-431.

Stinson, D. W. (2006). African American Male Adolescents, Schooling (and Mathematics): Deficiency, Rejection, and Achievement. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 477-506.

Tate, IV, William F. 2008. "The Political Economy of Teacher Quality in School Mathematics: African American Males, Opportunity Structures, Politics, and Method." American Behavioral Scientist 51, no. 7: 953-971.

Narrative Continued: Background from the Historical Perspective

When Homer Plessy refused to move from an all-white railroad car to the legally segregated black railway carriage car (1896) he set into motion the Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) 50 years later overturning separate but equal laws and the democratic right to adequate public education for all students. The long battle for academic equality for African Americans still exist today in many forms including stereotype threats (Steele, 1995), lack of culturally relevant pedagogy (Leonard et.al 2010) and segregation called tracking. Knowing that “students won’t learn what they are not taught” (Oakes 1990) the quality of science and mathematics education depends to a very large extent on the capabilities of science and mathematics teachers (Weiss, 1987).

Still the many programs aimed at educating all students have left women and minorities behind. Women’s education was initially confided to the three c’s – cleaning, cooking and child-rearing (Noelle 2010) and it wasn’t until the end of the 1700s that grammar schools allowed girls. These three c’s applied to all women, until the Women’s Movement started in the 1800’s and the Equal Rights Amendment facilitated the escape from traditional societal women roles. Most African American women would have to wait until the Civil Rights Movement to move primarily from domestics to other fields like nursing (my mother) or business owners and entrepreneurs like Lydia Newman (hair brush) .

Women like Patsy Sherman (one of the patent holders for scotch guard) and Grace Hopper (one of the developer of computer language COBOL in 1960 for the Navy) are products of the earlier tenacity of women in history. Gloria Conyers Hewitt was the 7th African American woman to earn her Ph.D. in math from the University of Washington. History has not been celebratory of these women and they are not held up to the light the same as their male or White (in the case of Hewitt) counterparts.

Knowing that with encouragement, access, highly qualified teachers and institutional support women, especially African American women can be successful in math and any other discipline we move toward why this problem exists.

References

Leonard, J., Brooks, W., Barnes-Johnson, J., & Berry, I. I. I. R. Q. (May 01, 2010). The nuances and complexities of teaching mathematics for cultural relevance and social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, 3, 261-270.

Noelle, K. (2010) The history of women’s education in America. http://www.ehow.com/about_6729065_history-women_s-education-america.html

Oakes, J. (1990) Multiplying inequities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (January 01, 1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 5, 797-811.

Summary of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954)

Weiss, I. (1987) Report of the 1985-86 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education. Research Triangle, NC: Research Triangle Institute.

Still the many programs aimed at educating all students have left women and minorities behind. Women’s education was initially confided to the three c’s – cleaning, cooking and child-rearing (Noelle 2010) and it wasn’t until the end of the 1700s that grammar schools allowed girls. These three c’s applied to all women, until the Women’s Movement started in the 1800’s and the Equal Rights Amendment facilitated the escape from traditional societal women roles. Most African American women would have to wait until the Civil Rights Movement to move primarily from domestics to other fields like nursing (my mother) or business owners and entrepreneurs like Lydia Newman (hair brush) .

Women like Patsy Sherman (one of the patent holders for scotch guard) and Grace Hopper (one of the developer of computer language COBOL in 1960 for the Navy) are products of the earlier tenacity of women in history. Gloria Conyers Hewitt was the 7th African American woman to earn her Ph.D. in math from the University of Washington. History has not been celebratory of these women and they are not held up to the light the same as their male or White (in the case of Hewitt) counterparts.

Knowing that with encouragement, access, highly qualified teachers and institutional support women, especially African American women can be successful in math and any other discipline we move toward why this problem exists.

References

Leonard, J., Brooks, W., Barnes-Johnson, J., & Berry, I. I. I. R. Q. (May 01, 2010). The nuances and complexities of teaching mathematics for cultural relevance and social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, 3, 261-270.

Noelle, K. (2010) The history of women’s education in America. http://www.ehow.com/about_6729065_history-women_s-education-america.html

Oakes, J. (1990) Multiplying inequities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (January 01, 1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 5, 797-811.

Summary of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954)

Weiss, I. (1987) Report of the 1985-86 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education. Research Triangle, NC: Research Triangle Institute.

Narrative Continued: The Controversy

The consensus that African American girls are inferior in mathematics has been persistent in our society. This internalized conception has conditioned them to believe they are not built to be math literate and are lacking the ability to enter fields and careers that are math based (Leonard 2010). There have been various explanations including a history of race issues, uneven parental influence, intellectual differences, or shortage of high-quality teachers and schools (Oakes 1990).

We have witnessed girls tracked into the lower, less challenging math classes early on thereby diminishing their access to higher level classes in high school. As we continue to move toward greater and greater computer literacy, we also must require high level of critical thinking skills to fill the future needs of technology and science (Oakes 1990). Critical thinking skills can be taught and in our experience, math is one subject that does that very well.

Between the ages of 10 and 18, adolescence males and females move through cycles of change. As they are working on differentiation of their in and out groups they are also working on their self-identity (Tajfel 1982) and place in the social order (Evans 2010) . During this time adolescence girls have an even harder time maintaining their self-esteem (Kusimo 1997). When you add on the challenge of identity creation to the minefield of the teenage years, its’ no wonder there are challenges. Girls have been led to believe that males are better than girls in math and have verbalized this belief in a study of girls in transition (Kusimo 1997).

Evans, A. B., Rowley, S. J., Copping, K. E., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (April 01, 2011). Academic self-concept in Black adolescents: Do race and gender stereotypes matter?. Self and Identity, 10, 2, 263-277.

Kusimo, P. S., & Appalachia Educational Lab., Charleston, WV. (1997). Sleeping Beauty Redefined: African American Girls in Transition.

Leonard, J., Brooks, W., Barnes-Johnson, J., & Berry, I. I. I. R. Q. (May 01, 2010). The nuances and complexities of teaching mathematics for cultural relevance and social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, 3, 261-270.

Oakes, J. (1990) Multiplying inequities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press.

We have witnessed girls tracked into the lower, less challenging math classes early on thereby diminishing their access to higher level classes in high school. As we continue to move toward greater and greater computer literacy, we also must require high level of critical thinking skills to fill the future needs of technology and science (Oakes 1990). Critical thinking skills can be taught and in our experience, math is one subject that does that very well.

Between the ages of 10 and 18, adolescence males and females move through cycles of change. As they are working on differentiation of their in and out groups they are also working on their self-identity (Tajfel 1982) and place in the social order (Evans 2010) . During this time adolescence girls have an even harder time maintaining their self-esteem (Kusimo 1997). When you add on the challenge of identity creation to the minefield of the teenage years, its’ no wonder there are challenges. Girls have been led to believe that males are better than girls in math and have verbalized this belief in a study of girls in transition (Kusimo 1997).

Reference

Evans, A. B., Rowley, S. J., Copping, K. E., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (April 01, 2011). Academic self-concept in Black adolescents: Do race and gender stereotypes matter?. Self and Identity, 10, 2, 263-277.

Kusimo, P. S., & Appalachia Educational Lab., Charleston, WV. (1997). Sleeping Beauty Redefined: African American Girls in Transition.

Leonard, J., Brooks, W., Barnes-Johnson, J., & Berry, I. I. I. R. Q. (May 01, 2010). The nuances and complexities of teaching mathematics for cultural relevance and social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 61, 3, 261-270.

Oakes, J. (1990) Multiplying inequities: The effects of race, social class, and tracking on opportunities to learn mathematics and science. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press.

The Narrative: An Introduction

As women with different success in the field of mathematics, my partner and I are personally invested in what are some of the reasons why this is the case. One of us is attached to the cultural and racial stereotype of African American women and the other was raised in an environment satiated with mathematicians and academic encouragement. This dynamic has made for interesting research collaboration. When researching the topic we specifically we wanted to answer the question “Why are African American females not successful in mathematics?” This led us to ask subsequent and larger questions of why are African Americans not successful in mathematics and more specifically why are females not successful in mathematics?